Top 5 Life Lessons I Learned From Investing

Timeless wisdom that has changed the way I live my life

It has been six years since I started my investing journey. Over that time, I’ve experienced what seems like a decade of investing lessons with the COVID crash, followed by a bubble in speculative growth and then the 2022 bear market.

The focus of this article will be to discuss life lessons that I’ve learned over this journey. As a growth investor, I develop mental models for how the world works and develop and test hypotheses derived from those mental models to figure out where companies will be years down the road, investing when our view of the future is different from what is priced in.

There is a reason why Charlie Munger talked about the art of stock picking as a subdivision of the art of worldly wisdom. The best investors are often multidisciplinary thinkers because markets, businesses, and economies are all influenced by a wide range of factors spanning psychology, sociology, mathematics, economics, history, and technology.

It is for this reason that I believe one’s journey to becoming a better investor is also a journey of intense introspection and self-improvement.

After reflecting on my mistakes and wins, I’ve narrowed it down to five life lessons I’ve learned from investing that I believe anyone can benefit from.

1. Process > Outcomes

You would never be able to tell that Warren Buffett is the world’s most successful investor with a net worth of $150B by the lifestyle he leads. He still lives in the same modest home he bought for $342K inflation-adjusted in 1958, drives a Cadillac XTS, is famed for drinking multiple Cokes and eating breakfast at McDonald’s on the way to work every day, and used a $20 flip phone until 2020.

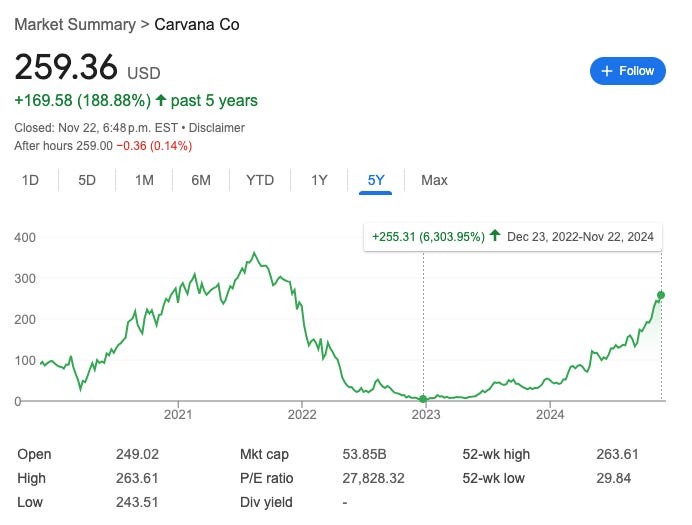

The most financially successful people in the world are almost never motivated by money. Jensen Huang, founder of Nvidia with a net worth of $130B, said he wouldn’t have started Nvidia if he knew how hard it was going to be. Similarly, Ernie Garcia III, founder of Carvana, said that no amount of money was worth weeks of sleepless nights as he fought to save his company from potential bankruptcy in 2022.

I believe a core reason this is the case, is because a motivation driven by money tends to lead to a focus on short-term outcomes over long-term improvement. In investing, the outcome tells us nothing about the probabilities; you could have simply gotten lucky or unlucky. The only way to make money consistently in investing is to develop a repeatable process that delivers good outcomes most of the time and accept that you will still lose money by getting unlucky sometimes.

When I worked as an analyst at Saga Partners, my portfolio manager rarely would ask why a stock was up or down on a given day or ask where I thought a stock would trade in the next 6 months. Rather, almost all of our energy was directed at understanding the long-term drivers of business outcomes and all incremental data points were filtered by asking whether they would affect where the company would be in 5 years.

This allowed us to accumulate knowledge that had a long shelf-life, such as developing mental models, identifying competitively advantaged business models, and studying new industries. This allowed us to compound learning at a faster rate compared to those who tried to predict the next quarter to the exact decimal.

Similarly, Clayton Christensen, a Harvard professor and influential business strategist, observed in his Theory of Disruptive Innovation that successful companies lose to disruptors by making decisions that will maximize profitability in the short-term.

For example, Blockbuster didn’t copy Netflix’s DVD-by-mail as it would have eliminated the significant profits they were making from late fees. Netflix ended up using DVD-by-mail to establish a foothold and eventually expand into streaming which led to Blockbuster’s bankruptcy.

In a later Ted Talk, Christensen observed his Harvard Business School classmates making the same unintentional mistakes by focusing on short-term achievement. Taking an hour out of their day to go to their kid’s football game and cheer them on is surely not as important as taking another late night at the office to close an important deal right?

While this may be true in the short term, the long-term consequences of these achievement-oriented decisions were disastrous. His Harvard classmates were doing great by the 5th year reunion but as time passed, many of them got divorced, estranged from their kids, and suffered poor health as they unintentionally ruined their lives.

“The only real test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life”

- Naval Ravikant

In this insightful article by writer Michael Simmons, he notes that a single-minded focus on constantly setting and achieving goals prevents you from recognizing opportunities along the way, it leaves you empty once you achieve them, it limits your curiosity, and it can leave you feeling trapped and insecure.

Rather, I believe the key to becoming successful is to not chase success for its own sake. Instead, identify what you value and base your lifestyle around that. Along the way, stay open-minded and let your curiosity guide you. Success comes as a byproduct of that.

2. Choose Games Where You Have an Unfair Advantage

Profit is not a perfect measure of how much value a business adds to society, but it is the best measure that we have.

Being passionate about something is not enough if your goal is to be able to make a living from it. While it is certainly possible to make a living doing anything, the bar for playing video games at a professional level is much higher than pursuing accounting.

Game selection, which is a concept that I learned from portfolio manager Yen Liow, is the idea that you must choose a game that you can win repeatedly and is valuable.

One of the core mistakes that companies often make, is they focus almost exclusively on the demand side (customers spending more) rather than changes on the supply side (competitors spending less) but it is the latter that drives profit.

For example, when the price of oil is high, oil companies are incentivized to invest in new capacity to generate greater profit. However, competitors are likely to be doing the same, and thus when the price of oil inevitably crashes because supply has increased so much as a direct result of the overinvestment, everyone needs to lower prices in order to get the volume needed to pay for their new plants.

This concept is explained in-depth in the book Capital Returns, and the takeaway is to either invest when competitors and capital leave the industry or to invest in companies where their competitive advantages allow them to earn high returns on capital regardless of the point in the cycle.

In both cases, profit is created through both creating value and having a relative advantage so that you can capture it. Airlines have been a historically poor sector to invest in despite the value they create for society because it’s a brutally competitive business where efficiency gains by one player are often immediately matched by the next, and thus value accrues to the customer via lower prices, better service, or faster routes and not the business owner.

It is much easier to succeed when you pick valuable games where you have an unfair advantage.

As I mentioned previously, in Clayton Christensen’s Theory of Disruptive Innovation, disruptive companies often begin in overlooked and niche markets, delivering superior value before continuously moving upmarket.

Amazon started by selling books because they were cheap, always in demand and were so numerous that physical bookstores would never be able to replicate Amazon’s selection.

However, the infrastructure that they successfully scaled for books created an unfair advantage that led them to become the Everything Store. And the computing infrastructure that was built to support the Everything Store created an unfair advantage that eventually led to AWS, and most shareholder value ended up being created from AWS.

Another concept I’d pair with this is counter-positioning, from the book 7 Powers by portfolio manager Hamilton Hemler, which is when a disruptor adopts a new business model that an incumbent would find very difficult to copy.

For example, brick-and-mortar used car retailers like CarMax would find it incredibly difficult to compete against the selection, price, and convenience offered by Carvana’s online model without closing the majority of their brick-and-mortar locations and completely upending their P&L. In fact, they decided to exit home delivery recently, despite Carvana proving the validity of the model by significantly outgrowing them and earning higher margins.

Applying this to my career, I should choose to develop a skill that I am not only passionate about, but is also valued by society, that I have a natural aptitude towards, and that other people would find difficult to copy (perhaps due to a lack of awareness or a lack of risk appetite). The below graphic sums this concept up well.

I see myself as someone who is intellectually curious, stoic, highly analytical, an independent thinker, and an optimist. I could spend years trying to compete with millions of talented and passionate basketball players to become a top NBA player but my time would be much better spent becoming a great investor.

And in investing, I can leverage the fact I’m only investing my personal capital and have a long time horizon and high tolerance for volatility, to invest in situations where larger investors cannot or will not.

3. Play positive sum games

Over the long term, the stock market is a positive-sum game, where it’s possible for everyone to benefit. This is because stock prices are largely driven by earnings growth and return of capital over the long-term, where companies create value for society, are rewarded through profits, and can choose to return those profits to shareholders or reinvest it in driving further value/profits.

This is an important concept to remember as oftentimes, when you’re focused on short-term price action, it can feel like a zero-sum game, where profits are dependent on who can react the fastest to a new press release. Hyper-competitive people tend to view life this way, akin to a game of chess, where every one of your wins is someone else’s loss.

However, just as it can appear counterintuitive that the stock market is a positive sum game, so too can it appear counterintuitive that playing positive sum games is a faster pathway to success in the real world.

A big reason for this is our craving for status. From an evolutionary standpoint, being high status and respected in a group meant a higher chance of survival, with the loss of status being akin to a death sentence via ostracization.

However, status is inherently a zero-sum game. If I want to be the best at something, then no one else can, incentivizing me to sabotage others rather than help them. Politics is a zero-sum game because only one party can win. Becoming a social media influencer is largely also a zero-sum game, as attention is limited. This can result in behaviours like virtue signaling, cancel culture, or clout chasing.

However, you can still play a positive sum game using social media with the right intentions. When I started posting on Twitter in January 2020 and wrote my first Seeking Alpha article pitching Livongo Health as a long at the same time, my goal was not to make money as an influencer but rather to connect with like-minded peers, just as it is now. By doing so, I was able to land my first job on the buy-side working for Saga Partners and gained fame when Livongo rallied from the $28 I pitched it at to $150 less than 8 months later.

I was also able to build valuable connections, one example being a small Twitter DM group that I was a part of that included both fund managers and individual investors that were interested in or owned Carvana stock. We shared data on unit sales, compared notes on management meetings, debated on our projections, and thought through the bear and bull cases extensively. I firmly believed that we were the most well-informed owners, and being a part of this group likely helped everyone in it maintain conviction through a 99% drawdown when the world was screaming that we were crazy.

Erik Torenberg encapsulated this concept in his article on career feedback loops, where he states that networks are heat-seeking missiles for value. Rather than focusing on outreach and networking chats, we should instead build a rare and valuable skillset and share our knowledge openly, whether that is through social media, a newsletter, or doing conferences. And that will lead to greater success than if we try to build a network first and then develop specialized skills.

4. In Every Crisis Lies Opportunity

I believe the hardest part about becoming a successful investor is not picking great stocks, but rather holding them in the face of volatility. This doesn’t mean blindly holding and hoping for the best, rather it means staying objective in assessing new data without letting price action dictate your decisions.

I believe this intolerance of volatility, driven by uncertainty, is also the largest driver of market inefficiency.

The logic behind this is simple: the people who make the investment decisions are oftentimes not the people that own the capital. This principal-agent disconnect is the reason why from 2010 to 2020, according to DALBAR, mutual fund clients underperformed their active managers by four percentage points annually.

To use another example, the best-performing mutual fund of the 2000s, the CGM Focus Fund, delivered 18% annual returns between 2000 and 2010. However, its clients earned an average of -11% annual returns over the same period, a 29% shortfall! I don’t blame them, it’s hard to stay calm during crises as an educated investor, but it’s even harder when you’re a client and not sure what you’re invested in.

Volatility is inevitable if you desire high returns and invest in the public markets. Even the greatest investors have had periods of underperformance. Despite achieving a 19.8% annual return over 13 years, Charlie Munger was down over 53% in the 1973-1974 bear market, ultimately leading him to close his partnership as he couldn’t bear the pain the volatility was causing his investors.

During market crises, the most informed investors are often the ones selling, not buying, because their clients can’t handle the volatility and are redeeming.

The best investments of all time were made with the combination of an informational edge, forced sellers, and limited buyers.

My Carvana investment embodied all three: I had access to near-perfect data on weekly unit sales before they were reported through the major alt data providers like Yipit through Clarity Markets, many large funds such as Tiger fired their manager and sold their positions on the way down, and Carvana was so widely hated and believed to be going bankrupt that merely mentioning you were bullish on it carried severe career risks.

Just as your decisions during bear markets make or break your track record, so too do periods of struggle in your life.

“The Chinese use two brush strokes to write the word 'crisis.' One brush stroke stands for danger; the other for opportunity. In a crisis, be aware of the danger--but recognize the opportunity.”

-JFK

Japan almost overtook the US as the world’s largest economy just 40 years after their country lay in ruins following WWII.

In 1978, when Deng Xiaoping opened the door for foreign investment in China, China was one of the world's poorest countries, with a per capita GDP that was one-tenth of Brazil's and one-fortieth of the U.S.'. Since then, they’ve lifted 800 million people out of poverty and have become the world’s second-largest economy.

To take a recent example, Carvana became a much more efficient business after its near-bankruptcy experience, realizing profit margins higher than ever before.

Almost no one who became successful got there without enduring struggle.

Charlie Munger went through a divorce, the loss of his first child, and blindness in one eye after a botched surgery and went on to become one of the most respected investors ever

JK Rowling was a single mother on welfare and got rejected by 12 publishers before she became one of the most successful authors ever

Apple, Amazon, Tesla, and Nvidia were all close to bankruptcy in their early years yet have become among the most valuable companies in the world today

These stories were an inspiration as I held Carvana through a 99% drawdown and a 70x rally.

I reported my portfolio performance publicly, despite enduring a nearly 80% drawdown, and publicly defended it on podcasts and Twitter at a time when it seemed inevitable to the world that it was going bankrupt.

I believed it to be a highly asymmetric bet on a generational company and management team that was going through some temporary challenges. There was always a risk that I could have lost it all, but I believed I was in a unique position to make that bet as I was young and could afford to take a long-term view.

“Everything that is not forbidden by the laws of nature is achievable, given the right knowledge”

-David Deutsch

Everyone goes through periods of struggle in their lives. However, your reaction to it is what defines its impact on you. No situation is completely good or completely bad, it’s only through the lens we label it that makes it so.

One of my favourite heuristics is to ask myself “what if it was a gift?”. Perhaps you lose your job, perhaps you go through a breakup, perhaps you lose a lot of money in the market. No matter how bad it may seem in the moment, it’s your reaction to it over the following weeks, months, years that will define its ultimate impact on your life.

5. Approach Your Life Through First Principles

If the most important skill to become a successful investor is holding through volatility, then the skill that best enables that is the ability to think through first principles.

The objective of an investor is not to avoid risk altogether, but rather to price it properly. Everyone wants to invest in companies with strong balance sheets, that are not cyclical, that have recurring revenue, that are highly profitable, and that have great management teams. These traits enable high base rates of success.

Because these companies are so predictable, investors are willing to pay a high valuation and look further out into the future. This could work out, but the downside could be high if the narrative ever changes. A low-quality company can be low risk at the right price, and a high-quality company can be high risk at a certain price. Of the top 10 most valuable companies in 1995, none are still in the top 10 today.

The simplest thing in the world would be to simply buy well-known “great” companies like the Magnificent 7 and go to the beach. This approach is likely to protect you against financial ruin, but it almost certainly guarantees that you will never become significantly above average either.

If you want to be more successful than most people, then you need to approach life differently than most people and the best way to do that is through first principles thinking. This involves breaking down a problem into its component parts and then building it up from there. This allows you to question every single assumption you originally had and generate unique new approaches.

For example, when Elon Musk wanted to build the first SpaceX rocket, he quickly discovered the cost of purchasing one was up to $65M which seemed exorbitant. He broke down each part of what the rocket was made of and discovered that the actual material cost was just 2% of the typical price.

The parallel that lies between becoming more spiritual and growing as an investor is the ability to take a step back and recognize that our thoughts don’t define who we are. When we label ourselves or the world around us, we are falsely equating truth with perspective. As an investor, the beliefs that hurt us the most over the long term are the ones that we take for granted the most to be true but turn out to be false, and likewise, create the most opportunity if you can discover and disprove such beliefs.

“The most dangerous phrase in the English language is ‘we've always done it this way’”

-Grace Hopper

The most obvious way to apply first principles thinking at an individual level is to live your life based on your personal values.

When we don’t know what we want, we tend to pursue society’s markers of status such as wealth, fame, and power. However, these external sources of satisfaction often provide fleeting happiness and many people discover that once they achieve them, they are still left feeling empty.

As the chart below shows, no matter how much you earn, you always want more to feel happy. This is driven by factors like lifestyle creep (spending more as you earn more) and having a richer peer group to compare yourself to (leaving you still feeling inadequate).

Through self-determination theory, academic psychologists have suggested that the three things that provide internal satisfaction to people are our need for autonomy (feeling in control), competence (confidence in your ability to complete tasks), and relatedness (feeling connected to others).

So, whether that be starting your own company, traveling the world, or starting a family, don’t be afraid to take risks and live a life true to yourself as there is no true blueprint for success.

Conclusion

Take a step back and ask yourself, if you were 80 years old and looking back on your life, what would you be the most proud of? What would you regret not doing the most? From there, you can get a sense of what your values are.

Try to build a lifestyle that enables you to realize those values. Don’t compare yourself or listen to others who don’t share the same values you do, but rather put your authentic self out to the world and seek to give without expecting anything in return.

Give your all to whatever it is that you want to do and pursue mastery. Stay relentlessly optimistic and open-minded and you’ll have the strength to grow from every challenge that you may encounter.

Most of all, stay curious and commit to lifelong learning and self-improvement. As Charlie Munger said, “Spend each day trying to be a little wiser than you were when you woke up”.

Thanks for reading,

Richard

The focus of this free newsletter is on the intersection of tech, healthcare, and investing. My next post will be a deep dive into the US healthcare industry.

If what I’m writing about resonates with you, feel free to subscribe and consider sharing with others who might benefit.

If you are getting a lot of value from my work, paid subscriptions are always appreciated.